Usually when an artist writes about his or her own work, they’re either explaining, or defending, why they did what they did and how they got there. But with the 2007 book Passing the Torch, by a Houston artist named Bob Fowler, I don’t walk away knowing any more about Fowler’s work or why he made what he made. But the term ‘passing the torch’ implies a continuity, and it’s a great pun for a how-to book about metal sculpture and all the tips and tricks Fowler learned in his 50 years as a working artist. According to its back cover, the London Financial Times called the book “Vigorous.” I’m not aware of any other artist-penned book like it. It is dry, abrupt, and to the point. There’s no pussy-footing around the subject – which is the actual making of art. It’s a bold and admirable work that deserves a closer look since its original publication date.

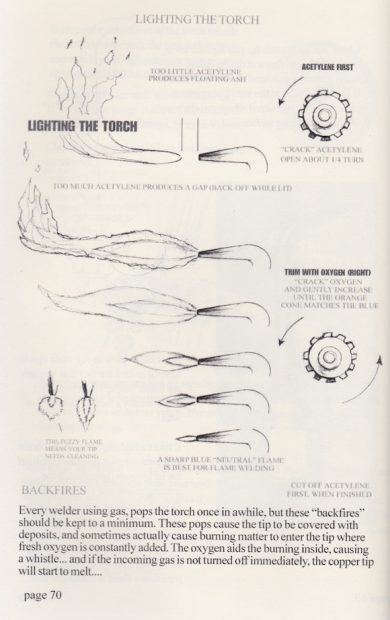

I came to this book through a separate work project dealing with one of Fowler’s sculptures here in Houston. I had never heard of him (and he died in 2010), so the book, which has been out of print and is sporadically available on Amazon, seemed like a good place to start to get to know Bob. What I found was a meticulous, resourceful, and confident artist. Meticulous: He not only describes various welding techniques, but he starts with such basics as how to light a welding torch. Resourceful: He not only illustrates how-tos for building mural-sized stretcher bars for architectural commissions, but he also lays out plans for building fountains and gates. And confident: It takes balls to write and self-publish a book with the subheading: “…everything you need to know about modern metal sculpture as applied to public and private art.” Everything. The book weaves between advice and moments of the artist’s self-reflection. The true beauty of the book lies in its interspersed practicalities that come from an artist who was at it for years, learning on the job.

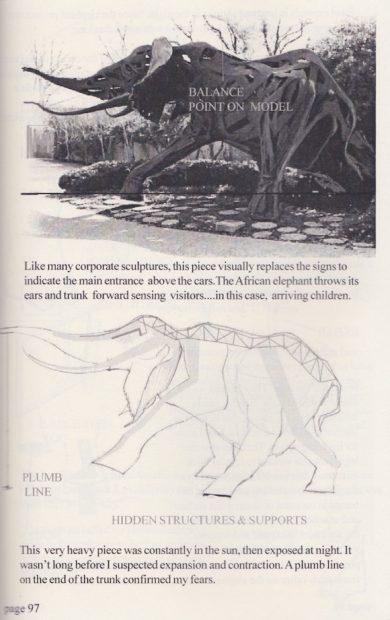

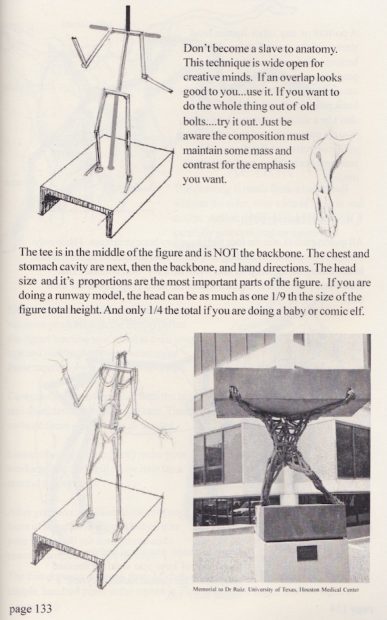

Bob Fowler was based in Houston for most of his art career, and he made art full time starting in 1963. He was also a teacher, an aviation illustrator who contracted with NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center during the Mercury program, an avid scuba diver, and a writer. “The best part of my education didn’t come from schools or Universities. It came from painting full-color illustrations of the dreams of aircraft and NASA engineers.” His unique, twisted metal works, many of which revolve around animal imagery, are spread throughout the Houston, most notably the African Elephant sculpture at the entrance of the Houston Zoo. Fowler’s work has been exhibited and commissioned internationally, all while he continuously revised his technique.

The book starts out strong, with an admonishing paragraph about why you need a tax ID number (“Despite rave reviews and long lists of one-man shows, an artist is in the business of selling art and the tax man will show up…”), and how to organize your workshop (“Unless you are a sideshow freak with three arms you’d better plan your space well”). Early on in Chapter One, the reader lands on a section titled “Your Mental Health: Failure and Depression.” Kicking it off with a quote by Thomas Edison, Fowler explains that failure is part of the artistic process, and if your work fails it doesn’t mean you are a failure. He goes on to explain that he’s lost two close friends to suicide; it seems that the impact of failure is a topic close to his heart. He lists his six customized anti-depression rules, one of which is: “Approval of your metal sculpture by someone else has nothing to do with the quality of the product. Self-approval of your product does.”

After all, welding is a lonely way of working. When you weld, your extremities are covered with a thick, heat-resistant gear. You wear a masking helmet that shields your eyes from the bright spark of the welding torch (“…welding is worse than staring directly into the sun.”). You’re already hot, and you add fire, and the heat radiates from the steel. It must be the most miserable way of making art, especially in Texas. And the very thing you’re creating is what you are protecting yourself from, while you’re fully encapsulated with your thoughts. Fowler’s answer to the aching question on any artist’s mind while toiling away in their studio — Am I Making Art? — is simply: “That’s literally none of your business.”

“Far too many potential artists fail because they get caught up in the Art Sceneand neglect the making of art. Awards of any kind are a great ego trip. Unfortunately some of them are totally meaningless and some of them are not even noticed by your peers or good dealers.”

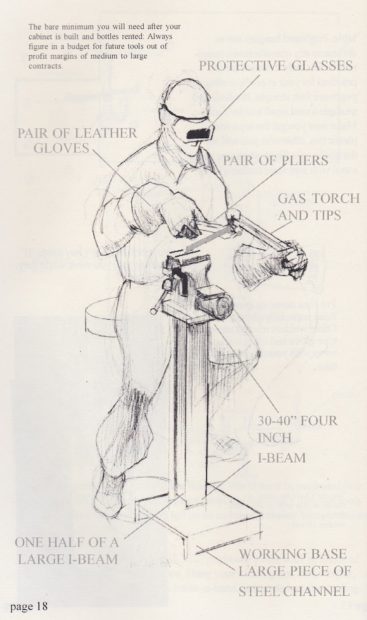

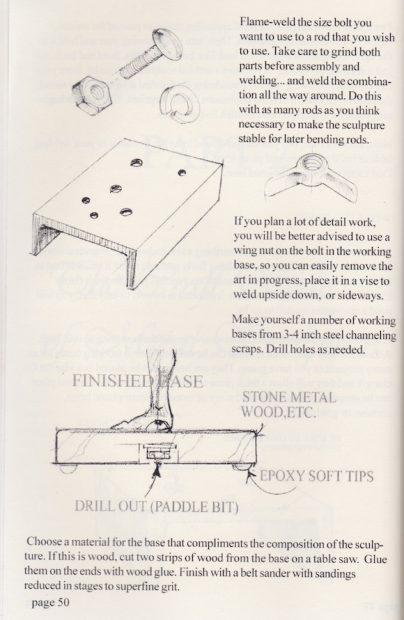

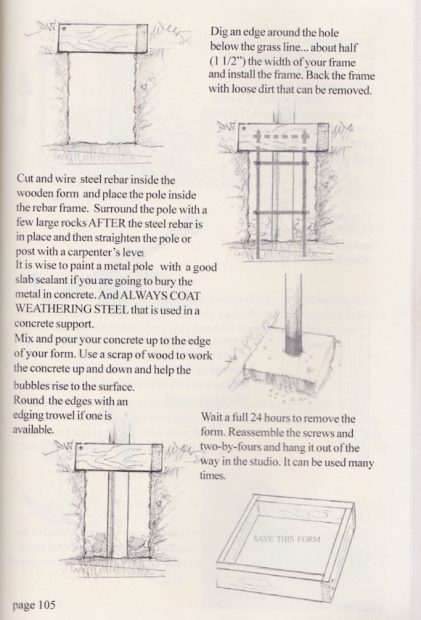

In addition practicalities like how to light a torch and how to prevent backfires, Fowler spends a lot of attention on bases — working bases versus finished bases. “No matter if you are working on something a few inches high or several stories in size, you will have to have something fairly portable to put it on.” This metaphorically grounds Fowler’s focus on what it means to be an artist, and he knows it. “You can’t learn to be creative without a sound base of real knowledge to take creative liberties with.”

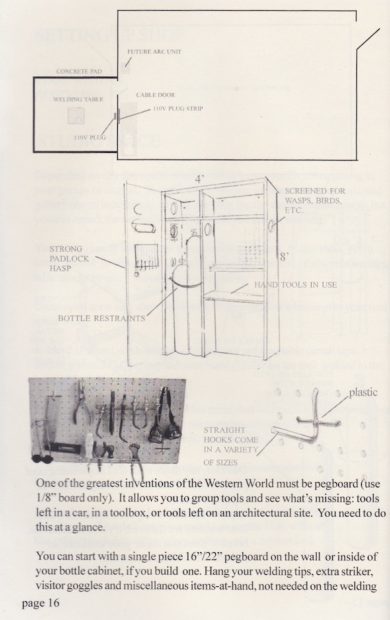

Rather than outlining an idealized studio setup or romanticizing an expansive warehouse workshop, Fowler starts with, and continuously returns to, the idea of just converting your garage into a welding studio or using your bedroom as a studio: “Set up a drawing space [an unpainted door, laid flat?] next to a window with good light.” He does warn artists — several times — that you should check your neighborhood’s restrictions so that you don’t end up paying a fine.

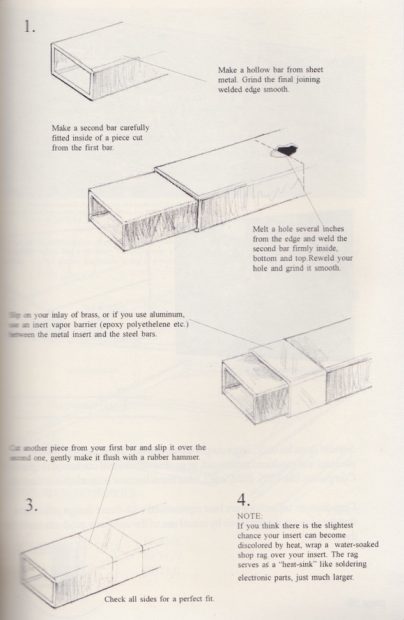

In terms of materials, Fowler explores various methods for combining dissimilar metals, through inlays or using a hidden riveting system. But he also makes a great case for using tin as raw material: “Once upon a time you could stop off on the way from your day job Friday evening and pick up a six pack of beer, drink it, then take it into the garage/studio, work with it, and have a gallery piece ready to go at the beginning of the week.” Even though beer cans are aluminum these days, vegetable cans could work in a pinch.

Drawing is a big part of a sculptor’s practice. “Needing a quiet place to draw is a pleasant myth invented by Sunday painters, bless their hearts.” Making something 3D usually means sketching out your idea first and articulating it from all angles, so why wait to till you sit down with a fancy sketchpad? “Most hotels have several return address envelopes in the room. Use one or two for thumbnail ideas that you want to remember and redraw them more completely when you finally reach your studio and your sketchbook.” He advises to turn over the paper near a window to see a hint of the composition in reverse.

And all those drawings (and photos) can lead to etchings and lithographs, which can be sold, perhaps more easily than the finished sculptures. In the book, the practicality Fowler brings to the making of things is carried though to the dreaded “business” of being an artist. He lists ways to make extra money to keep your studio practice viable. For example, he suggests that once you do have that big warehouse space, build a couple of plastic-covered painting racks (“birds get in your studio”) and rent them out for storage space to your painter friends.

“Rent these racks to fellow artists, and chalk their names on the floor. Two racks with double and single spaces 8’ high will do for the average painter. They can rent second and third spaces as necessary. Make sure your renters know, in writing, that the paintings are not insured by your coverage. Set up a win-win situation by dividing your rent by the number of rentable racks you have.” Brilliant.

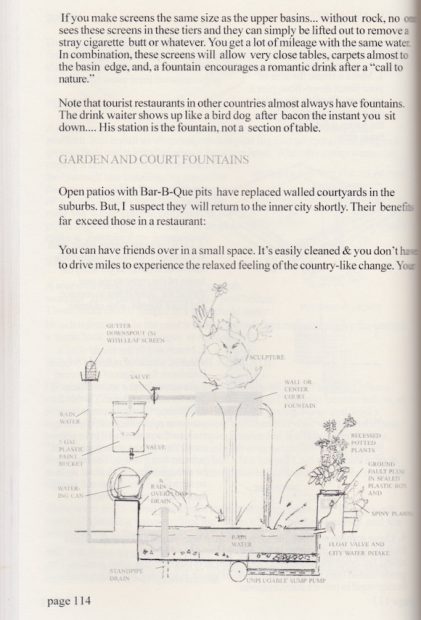

After all, you’ve gotta eat. So why have an aversion to making something functional? If it keeps you in the studio and out of an office, maybe that’s a good thing. Fowler outlines how to make useful things and commissions: Secure mailboxes, decorative gates, and even fountains: “Why do you quit going to a great restaurant if the food remains good: Noise? Lack of privacy? No place to sit and talk while waiting for a table? Fountains can cure all of the above and more.”

The book is dedicated to John Tucker, who was the first accredited art appraiser in the state of Texas. In the dedication, Fowler recounts a court case he lost. Evidently, a church had contracted Fowler for some work, but the church’s bishop didn’t honor the contractual provisions. There were no penalties for non-compliance outlined in the contract, so there was nothing the court could do. John Tucker attended this hearing, and afterwards strongly urged Fowler to get a copy of the trial transcripts. Fowler, feeling low, thought it was a waste of money to pay for that. Fowler and Tucker had a heated argument about it in front of the courthouse, and Fowler writes that it was this altercation that made him realize, in the end, the importance of keeping records, of writing things down — of passing on the torch.

According to his widow, Diane Fowler, Bob was back in the classroom teaching part-time in the mid-2000s when he realized that he couldn’t find a publication for students that would relay all this practical and technical knowledge that was also humanized with discussions of the personal and the professional. Passing the Torch is what he envisioned. The book, edited by Diane, was self-published through the online service lulu.com a just few years before Fowler’s death.

Welding technology was not mainstream until after World War II. And electric welding, and its immediacy, was a new development as Fowler started making art. An abundance of metal and space in Houston when he started out, plus his involvement with the space program, likely encouraged his curiosity along his art-making path. “The welding media as art is as new as modern America is. It is marked more by future possibility than history.”

Personally, I love how-to guides by and for artists. They’re a simplified way of understanding the physicality of our world. And new technologies need instructions. I hope more artists will join Fowler in contributing to the how-to genre, especially since materials are their thing. A crucial part of making art is working with materials: Brush to canvas. Pen to paper. Torch to metal. Who better to document the practical and cultural shifts in materials and processes than artists? What is the best way to clean a paintbrush? (Or, Why make a fountain?) I say leave it up to artists to tell the story, one how-to guide at a time.

To purchase a copy of Bob Fowler’s ‘Passing the Torch,’ contact Diane Fowler at dihrufowler@gmail.com, or try Amazon.

Published on Glasstire November 10, 2018